|

|

Wiseblood Books fosters works of fiction, poetry, and philosophy that wrestle us from the ruse of distraction; find redemption in uncanny places and people; articulate faith and doubt in their incarnate complexity; dare an unflinching gaze at human beings as "political animals"; and render well this world's sufferings without forfeiting hope—all of this with an unflinching gaze, wide-eyed. [read more HERE]

|

Recent Releases

|

|

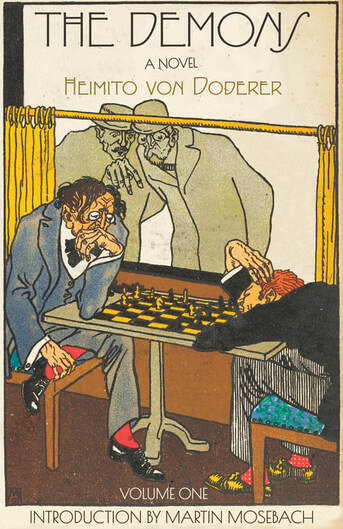

The Demons

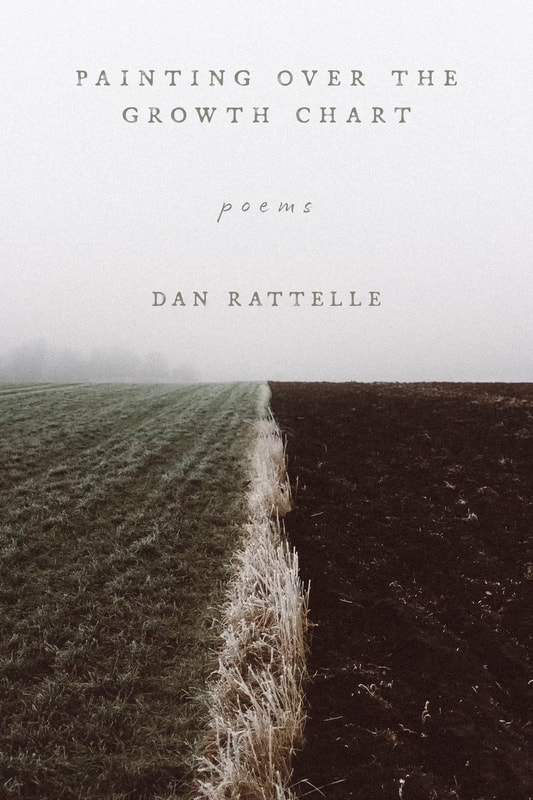

Heimito von Doderer Regarded by many as the most important Austrian novel of its era, Heimito von Doderer’s The Demons is a sweeping portrayal of Viennese society on the cusp of catastrophic and irrevocable change. Narrated by retired civil servant Georg von Geyrenhoff, this monumental work takes readers on an intimate, multi-layered tour through Vienna’s cafés and kitchens, bedrooms and back alleys, modest apartments and artist’s ateliers, palatial parlors and wooded parks, a basement, and a burning palace. The paradoxes of this novel–which von Doderer wrote and revised over the course of twenty five years–are born from the paradoxes of Europe after the first world war, with its superficial peace and order layered over a festering decline and despair that erupts into World War II. But amidst the background of Vienna’s historical July Revolt, which culminated in the Palace of Justice set aflame, The Demons asks us to see significance in even the smallest kitchen fire too–to see the souls beneath the world-historical heavings. The Wiseblood Double-Volume contains both an extended introduction by Martin Mosebach, “The Art of Archery and the Novel: The ‘Commentarii’ of Heimito von Doderer,” and an appendix with von Doderer’s lectures on the “Foundations and Function of the Novel.” Both have been ably translated by Dr. Vincent Kling. Painting Over the Growth Chart: Poems

Dan Rattelle Dan Rattelle’s Painting Over the Growth Chart is an accomplished and engaging collection, shot through with a recurrent sense of dislocation, of “not getting there from here,” dispelled by vivid moments of transcendence, as in “Believer’s Baptism,” when the “grave was swept away” and water ran “like blood down your thigh.” These appealing poems hang between hope and anguish, always reaching for consolation in friendship, fond memories, faith, and a warming glass of cheer. Like the potter he celebrates, who “pulls, as though from nothing, / the cup,” Rattelle summons memorable poem after memorable poem. —Ernest Hilbert, author of Storm Swimmer, and Winner of the 2023 Meringoff Poetry Award Dan Rattelle’s book is rooted in New England, offering a searching view of the region and its people that is unsparing yet humane. Some lyrics read like narrative fragments haunted by what has been withheld from the page; others, like the brilliant series on tools and implements, invest their inanimate subjects with the power of heritage and even streaks of personality. With forebears like Frost unavoidably in the background, Rattelle’s first book revivifies traditional forms and scenes with exacting craft and distinctive insights. He has followed what Frost called “the old way to be new,” and his reward is equally that of the reader. —Robert B. Shaw, author of Emily Dickinson Professor of English Emeritus, Mount Holyoke College |

|

Memory's Abacus: Poems

Anna Lewis In this remarkable first collection, Anna Lewis wends her way through the ordinary spaces and cadences of everyday life, exploring how the past remains present through pattern and memory. Rhyme, repetition, and traditional verse forms—most notably, a strikingly original crown of triolets—probe what’s old and new in our modern-day experiences of family, motherhood, loss, and faith. These poems echo with blooms and tombs, windows and war, numbers and names, mythological figures and passing strangers. They collect and count, save and sift, inviting us to take pause, see, and savor what’s visible—and what’s invisible—on our shared and personal journeys through time and space. What else is there, Anna Lewis asks in her eponymous poem, “but this / one life, that’s more, / almost, than we can bear?” With hushed precision and flawless delicacy, the poems in Memory’s Abacus chart how close to unbearable life can be even as they celebrate its beauties. A line of laundry, spring petals, a child’s acquisition of language: all are occasions for ardent attention. What might seem everyday details build, in the architecture of this collection, into a construct as durably radiant as a book of hours or a liturgical calendar.Without a trace of sentimentality or sententiousness, Lewis offers us a guide to a life lived with gratitude and awe, with an attentiveness that misses nothing—not a season, not a death in the family, not the yard of the day care. Such a celebratory gathering of poems is itself an occasion for gratitude. -Rachel Hadas, author of Ghost Guest |

|

One Hundred Visions of War

Julien Vocance | Translated by Alfred Nicol | Preface by Dana Gioia The “One Hundred Visions of War” of Julien Vocance (1878-1954) comprise some of the first haiku written in the West. Where classical Japanese haiku traditionally speaks of the beauty of Nature, Vocance uses the form to a very different purpose, depicting the horror and brutality of armed conflict, as seen from the trenches during the First World War. Readers get a ground-level view of unimaginable slaughter. The value of Vocance’s poetry lies in its witness to the experience of the human being caught up in a battle which, as Wendell Berry put it, “the machines won.” Only imagine: an obscure soldier-poet pits his human art against overwhelming military technology, and his art survives. “Like Ungaretti and Apollinaire, Julien Vocance faced the instant karma of the First World War with outcries of visionary perception. Each flash of the battlefield, each haiku, is a compelling ode to what can go away in a second, and to what remains, even amid annihilation. One Hundred Visions of War is an essential addition to the history of modernist poetry. More importantly, it is an urgent and deeply moving read, each vision guided into English by the poet Alfred Nicol, who brings a keen eye, an exacting ear, and a consummate poetic intelligence to these pages.” —Joseph Donahue, Professor of the Practice at Duke University; author of the ongoing poem Terra Lucida [read more HERE] |

Fiction |

Monographs |

PoetrySeren of the Wildwood

Marly Youmans |

Classics |

DONATE!

|

"The late James Laughlin’s publishing house, New Directions, is the standard at the moment for contemporary fiction. When you see ND on the spine, you know that you’re getting a solid work that is actively engaged with contemporary literary concerns. It is still too early to tell what will become of the upstart Wiseblood Books, but such a strong entry as this early on is a sign that it is heading in the right direction."

—From M.A. Peterson's review of Wiseblood Books'

A Waste of Shame and Other Sad Tales of the Appalachian Foothills |